The two previous articles on Decarbonising Heat summarised the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)’s study of the costs of different solutions and looked in more detail into the most effective but also the most expensive of these solutions – heat pumps.

This article will look into the other main contender – the use of hydrogen instead of natural gas. Hydrogen can be distributed through the existing low-pressure gas distribution network once the on-going upgrade to polyethylene pipes is complete. The cost is divided between the production of hydrogen, its storage, high-pressure transmission, and the conversion of domestic and non-domestic boilers to work with hydrogen.

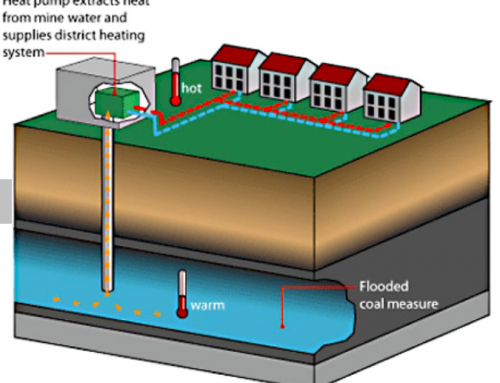

There are several ways to produce hydrogen but the report focuses on Steam Methane Reformation (SMR), in which methane (natural gas) is mixed with steam to produce hydrogen and CO2. The latter is then captured, piped and stored underground in depleted offshore reservoirs (CCS). The two processes are not perfect with the result that SMR requires 20 per cent more methane than would be required for direct use (other sources say more), while the CCS process only captures only 90 per cent of the CO2, although this may be improved in the future.

Hydrogen can also be produced by electrolysis using electricity from renewable sources, but the report considers this too expensive to be viable with today’s technology. A further option is to obtain methane from biomass gasification so that the overall process removes CO2 from the atmosphere. This is attractive but the amount of biomass that would be available for this purpose, and its cost, is quite uncertain.

The report envisions four major production centres around the UK with transmission pipelines being rolled out to local distribution networks from 2035, starting with the nearest and expanding progressively to the most remote. Counties are grouped in tiers, from one to six, one being the nearest. To even out supply and demand hydrogen would be stored in salt caverns over the summer ready to cope with winter demand.

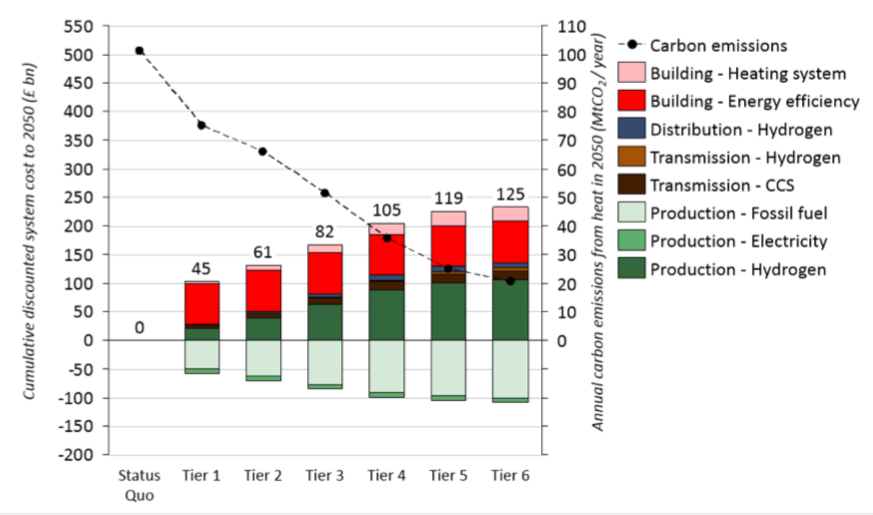

The resultant cumulative costs to 2050 are shown for each stage of the network expansion in the plot below, as are the CO2 emissions in 2050. It is assumed that unlike in the Status Quo homes are upgraded to medium efficiency (see Decarbonising Heat I). This saving in energy roughly counterbalances the extra methane needed to produce hydrogen so that the cost of hydrogen production roughly balances the savings from not using fossil fuel directly.

The vertical bars show the cost to 2050 above the Status Quo as the hydrogen network is rolled out over the country. The numbers above the bars show the net cost after taking into account the saving in fossil fuel. The black dots show the emissions for each case with the scale on the right. (from Cost Analysis of Future Heat Infrastructure Options by elementenergy and E4tech)

The plot shows that when all six tiers have been converted, CO2 emissions in 2050 are reduced to 20 Million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) per year, of which about half arises from CO2 not captured by CCS and half from homes that are off the gas network. This is more than the 7MtCO2/year predicted for the heat pumps but the additional discounted cost of £125bn is less. The annual heating cost per home in 2050 rises from £840 in the Status Quo to £970, which is £100 less than with heat pumps.

If biomass gasification is added, emissions can be reduced to 7MtCO2/year for nearly the same cost if about half the maximum predicted feedstock is used. If the maximum feedstock is used emissions can be turned negative, but costs rise sharply to £228bn because of the high cost of additional imported feedstock.

This all sounds attractive, but there are technical as well as financial uncertainties with the hydrogen solution. Hydrogen can be transported safely but less is known about safety in the home. CCS has been shown to work, but on a relatively small scale. Whereas the heat pump solution is expensive and more disruptive to homes, it deals in known technologies. The hydrogen solution is a big bet on a system whose practicality is unknown and which will most likely depend on importing natural gas (but then the heat pump solution will probably depend on importing some electricity).

For these reasons the NIC has called for trials to establish the safety of using hydrogen at the community scale by 2021 and to implement the complete chain for 10,000 homes by 2023. Elsewhere the Northern Gas Network has proposed a project to convert the Greater Leeds area to hydrogen by 2029 (Leeds H21 City Gate) and on the 22 November the Committee for Climate Change also called for more trials. Hopefully the results will provide clarification.

Reference: National Infrastructure Assessment 2018