The last year has been up and down for the Indian solar industry. It started well with some record low auction bids in February, for example Rs3.3 per kWh (£36 per MWh) for a project of 750MW in Madhya Pradesh. The project was accompanied by new payment guarantees and the introduction of a “deemed generation benefit”, in which the power producer is paid even if the electricity cannot be used because of grid problems. In addition the project is partly owned by the central government, which, with the other factors, gives greater assurance that bills will be paid.

Auction prices continued to fall in Q2, going below Rs2.5 per kWh. Then on 1 July the government introduced a new general sales tax, which increased the rate on solar panels from zero in most states to 5 per cent while also reducing the rate for coal. But positive news soon followed in August, when the Ministry of Power finally issued guidelines for solar auctions that included the guarantees and deemed generation benefit used in the Madhya Pradesh project.

In spite of this the number of auctions dropped significantly in Q3 for a variety of reasons. After years of steadily dropping prices, Chinese panel prices suddenly and unexpectedly increased. The low auction prices also caused some states to start renegotiation of previous power purchase agreements, while the new sales tax rate for equipment other than the panels turned out to be unclear.

To counter this the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) announced in November that it would auction 17GW of utility-scale projects between then and the end of March 2018. Given that India’s total installed solar capacity in December was 16.7GW this would be a very large increase, and represents about 55 million standard (1m x 1.7m) solar panels, or an area more than twice the city of Oxford. At the beginning of January commentators were writing about a comeback.

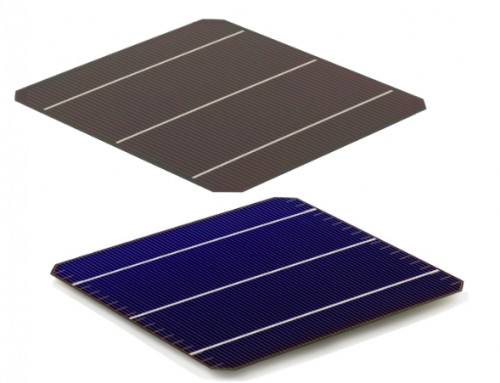

Then on 5 January, following an application by the five main domestic solar manufacturers, the Directorate General of Safeguards, Customs and Central Excise (DGS) recommended an immediate 70 per cent safeguard duty on solar cells and panels from China and Malaysia for 200 days. Given that India imports 90 per cent of its solar panels, different agencies have estimated that the cost of solar projects would increase by 25 and 40 per cent.

The DGS’s argument is that after the EU and USA introduced anti-dumping measures in 2013/15 China directed its excess solar capacity towards India. The latter used to have a Domestic Content Requirement but was forced to abandon this by the WTO in 2016 after a complaint by the USA. Since the price of imports has been falling for a long time (notwithstanding the increase in Q3 2017 reported above) the domestic producers cannot compete, and in 2017/18 expect to produce only 51 per cent of their 1.65GW capacity.

The safeguard duty is subject to a public hearing with the final decision taken by the Ministry of Finance. Many issues need to be sorted out, such as what happens to panels already ordered, but mainly the government has to decide its priority: is it to protect its panel manufacturers, or to protect the solar installation industry and help meet its ambitious solar target? But that is not the only problem. The Directorate General of Anti-Dumping and Allied Duties is separately investigating whether China, Taiwan and Malaysia have been dumping solar panels in India.

Whatever the outcomes, and until those outcomes are decided, the uncertainty itself will increase auction prices or reduce the number of offers, or most probably both. The Solar Energy Corporation of India (a branch of the MNRE) has already delayed one 2GW auction scheduled for 8 January.

Meanwhile 2017 saw no such uncertainty concerning installations as these are based mainly on auctions won the year before. India’s total capacity nearly doubled, with 7.6GW added to the 9GW at the end of 2016, and with a further 6.5GW in the pipeline. The target is 100GW in 2022 so there is still a long way to go.