By Barney Smith

Amidst all the excitement of last week’s Budget, there was, perhaps, one encouraging sign for the longer term. There does seem to be a growing realisation that the nuclear future is not all large plants, which are typically both over budget and way behind timetable: there may, indeed, ought to, be room for smaller plants as well. Their advocates say they would be quicker to bring into commission and, crucially, significantly cheaper if constructed on the modular principle.

It is not the case that this is an example of a new technology suddenly bursting on the market. The arguments in favour of small modular reactors (SMRs) are well known and indeed have been known for many years, ever since Rolls-Royce worked on the first generation of our nuclear submarines. Rather, in the last few years there has been a creeping realisation that the arguments for SMRs have more merit than previously thought.

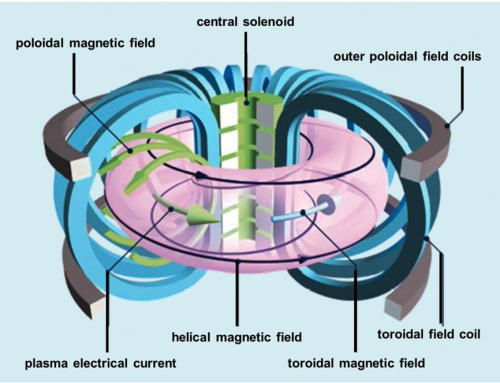

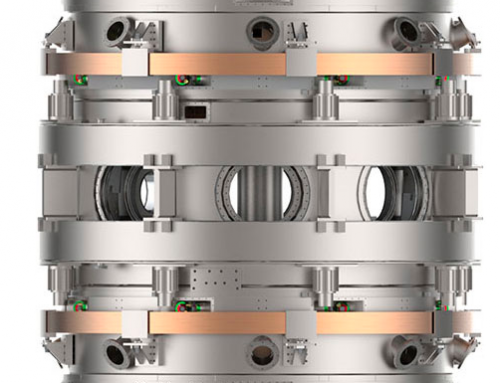

An SMR is defined as a nuclear device with a capacity of a few hundred MW and it is claimed that modular production could transform the present costly position on nuclear. With costs falling significantly, there could even be export possibilities.

www.rolls-royce.com

In his Budget Speech, as a sign, perhaps, of a “Change of heart”, the Chancellor announced that the Government has launched an open competition for small modular reactors, where companies can aim at reducing the construction risk inherent in larger projects by using factory-style production. The hope is that this will enable consortia, like that headed by Rolls-Royce, to put forward more detailed plans. To that end, the consortium’s reactor design is already being examined by the Government’s safety regulator, the Office for Nuclear Regulation.

Mr. Hunt also announced the launch of Great British Nuclear (GBN), a new body. He said that its’ major task would be to revive nuclear energy in the UK. For although the seven existing nuclear power stations produce far more electricity than the proposed modular sites (Up to 3 GW) six of them are due to be “retired” by 2030. And the problem does not end there for the remaining site, Sizewell, is due to be “retired” in 2035.It is acknowledged that one of the factors leading to cost overruns is that the existing sites are so big and so individualistic that there are few opportunities to learn from mistakes.

GBN is also to be tasked with ensuring that an increased percentage of Britain’s electricity comes from nuclear by 2050, as envisaged in last year’s energy security strategy. (It is hoped that the percentage will go up to roughly twenty-five per cent.) In addition, GBN is to help companies find suitable sites for nuclear power plants, thus developing what would become an important source of site proposals for the Government.

But that is for the future. For the present, a word or two of caution is advisable-there is no identifiable new money for nuclear or indeed for anything else, even though Mr Hunt expressed a wish to invest up to twenty billion pounds in carbon capture and storage capacity over the next two decades.