Another British offshore wind farm: turbine size has continued to grow. Image: By David Dixon, via Wikimedia Commons

This article first appeared on the www.climatenewsnetwork.net website

by Paul Brown

The costs of producing renewable electricity in the United Kingdom from wind and sun have dropped dramatically in the last four years and will continue to fall until 2040, according to the British government’s own estimates.

A report, Energy Generation Cost Projections, 2020, by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, shows that wind power, both on and offshore, and solar energy will produce electricity far more cheaply than any fossil fuel or nuclear competitor by 2025.

Costs have fallen so far and so fast that the department admits it got its 2016 calculations badly wrong, particularly on offshore wind farms. This was mainly because the turbines being developed were much larger than it had bargained for, and the size of the wind farms being developed was also much bigger, bringing economies of scale.

The new report avoids any comparison with the costs of nuclear power, leaving them out altogether and merely saying its cost assumptions have not changed since 2016.

Nuclear costs are a sensitive issue at the department because the cost estimates its report used for nuclear power in 2016 were optimistic, and although the report does not comment there have already been reports that they are expected to rise by 2025.

“For offshore wind, significant technological improvements (for example, large increases in individual turbine capacity) have driven down costs faster than other renewable technologies”

This is at a time when the government is yet to decide whether to continue its policy of encouraging French, Chinese and Japanese companies to build nuclear power stations in the UK, with their costs subsidised by a tax on electricity bills.

Although all the figures for renewable prices quoted are for British installations, they are internationally important because the UK is a well-advanced renewable market and a leader in the field of offshore wind, because of the large number of wind turbines already in operation.

The fact that large-scale solar power is cost-competitive with fossil fuels even in a not particularly sunny country means that the future looks bleak for both coal and gas generators across the world.

The prices quoted in the report are in pounds sterling per megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity produced.

For offshore wind the department now expects the price to be £57 MWh in 2025, almost half its estimate of £106 for the same year made in 2016. It expects the price to drop to £47 in 2030, and £40 by 2040. Onshore wind, estimated to cost £65 MWh in 2016, is now said to be down to £46 in 2025 and still gradually falling after that.

Nuclear cost overruns

Large-scale solar, thought to cost £68 in 2016, is now expected to be £44 MWh in 2025, falling to £33 per MWh in 2040. The output of the latest H class gas turbines is estimated by the department to cost £115 a MWh in 2025, although this is a newish technology and may also come down in price.

The 2016 report says nuclear power will be at £95 MWh in 2025, and although this year’s report says the prices remain the same Hinkley Point C, the only nuclear power station currently under construction in the UK, has already reported cost overruns and delays that put its costs above that estimate.

The 2020 report says: “Since 2016, renewables’ costs have declined

compared to gas, particularly steeply in the case of offshore wind. Across the renewable technologies, increased deployment has led to decreased costs via learning, which then incentivised further deployment, and so on.

“For offshore wind, significant technological improvements (for example, large increases in individual turbine capacity) have driven down costs faster than other renewable technologies (and will continue to do so).”

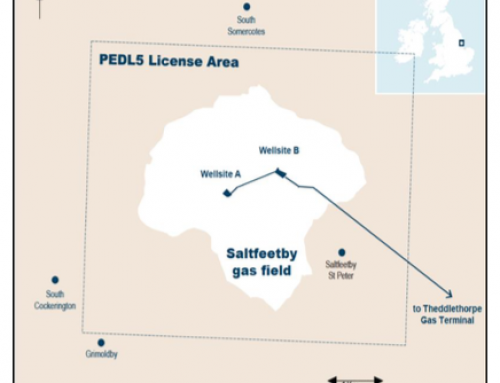

By coincidence, on the day the report was released, it was reported that two of the UK’s largest wind farms, off the east coast in the North Sea, are to double in size.

Better storage available

The energy giant Equinor agreed to lease 196 square kilometres of the seabed for extensions to the Sheringham and Dudgeon wind farms to double their capacity to 1,400 megawatts, enough to power 1.5 million homes.

Since the BEIS published the 2016 report the arguments about renewables have changed. Although the report does not say so, the intermittent nature of renewables is less of an issue because large-scale batteries and other energy storage options are becoming more widespread and mainstream.

Also, both the European Union and the British government are investing in green hydrogen – hydrogen from renewable energy via electrolysis – which could be produced when supplies of green energy exceed demand, as they did in Britain during the Covid-19 lockdown earlier this year.

In future, instead of this excess power going to waste, it will be turned into green hydrogen to feed into the gas network, to power vehicles or to be held in tanks and burned to produce electricity at peak times.

According to analysis by the research firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd, reported in Energy Voice, the cost of green hydrogen will drop by 64% by 2040,

About Paul Brown

Paul Brown, a founding editor of Climate News Network, is a former environment correspondent of The Guardian newspaper, and still writes columns for the paper