The year 2018 was good for solar energy companies. With one of the hottest summers in UK history NextEnergy Solar Fund (NESF) was able to generate 7.9 per cent more electricity than budgeted from its 60+ UK solar plants in the six months to 30 September 2018. Measurements of the actual solar irradiation suggested that electricity production should have been even more, but solar panels lose efficiency at the high temperatures experienced while in several cases the grid could not accept the extra power.

As a result the company is able to continue its policy of steadily increasing its dividend, with a target of 6.65p per share for 2018/19, versus 6.42p in 2017/18 and 5.25p when the fund opened in 2014.

During the same six months period the company added 14 solar plants to its existing UK portfolio of 55, giving it a total capacity of 657MW, which is 5 per cent of total UK solar capacity. NESF also owns 8 solar plants in Italy with a capacity of 34MW.

www.nextenergysolarfund.com

All this positive news has not been reflected in the share price, which is at about the same level as mid 2017. There could be several reasons for investors taking a less positive view. One is the transition away from subsidised solar assets. Until last year all NESF’s assets were subsidised by renewable obligation certificates or Feed-in Tariffs, which give the company a steady revenue. However since 2017 new solar plants are not subsidised, making new solar assets less profitable and driving up the costs of existing, subsidised, assets because the supply is now limited.

In July 2018 NESF bought its first unsubsidised operating solar plants (ten, with a capacity of 66.8MW), and has promised to announce its plans for construction of subsidy-free plants before the end of its financial year in March. In May 2018 NESF also made a first, tentative, investment in storage by purchasing two plants that had integrated battery systems, albeit of fairly small capacity.

Another factor that may be influencing investors is the future wholesale price of electricity. In its interim report NESF forecast higher prices in the short term but a low growth rate of 0.2 per cent before inflation in the long term.

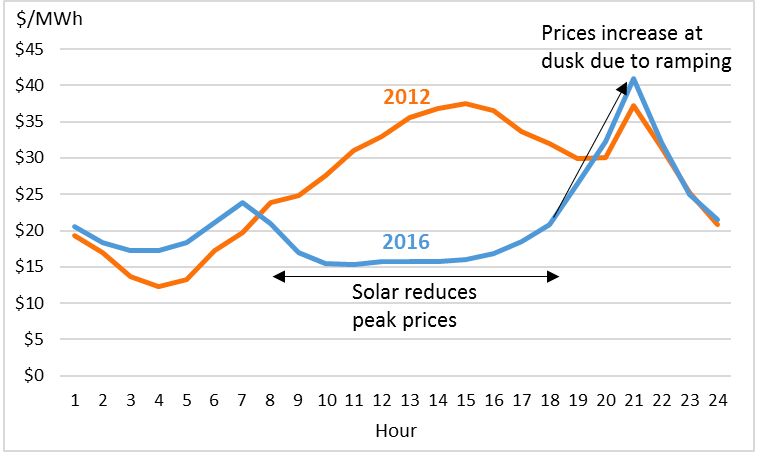

In estimating electricity prices the company also makes a “solar capture” reduction which takes into account the fact that market prices in daylight hours are less than the baseload prices on which future projections are based. As solar energy provides more of our electricity, the solar capture reduction will also increase, thereby reducing the price that NESF can charge for its power (see the California duck effect below).

NESF has produced a good return on investment since it floated in 2014, but it needs to adapt to the new world of subsidy-free solar power and increasing amounts of intermittent power. It is only slowly adapting to this new world.

The solar capture effect has been well documented in California, where the large amount of roof-top solar power introduced between 2012 and 2016 caused power prices in the middle of the day to drop dramatically followed by a very rapid increase in demand from the grid and price in the evening. This is the so-called duck curve, with the head representing the evening peak and the body outlined by the day-time curves (www.sparklibrary.com).