By Julian Singer

In an on-line event arranged by the Oxford Martin School on 1 March three experts explained how captured carbon could be stored underground and how much storage would be needed.

Carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS) is a part of all four IPCC[1]scenarios for reaching net zero CO2 emissions in 2050, and a major part of three of them. According to one analysis by the Global CCS Institute the world will need to capture and store 5635 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year (Mtpa) by 2050 to meet the goal. This is roughly equivalent to seventy per cent of the natural gas produced annually worldwide today, and is up from the 40 Mtpa captured and stored annually today. It is, therefore, a very large volume.

In this scenario 30 per cent is captured from coal-fired power stations mainly in non-OECD countries, in which India and China are prominent, and 30 per cent from natural gas, with a significant fraction used to produce hydrogen. Then there is 17 per cent for capture from biomass and another 17 from industry, mainly steel and cement.

www.globalccsinstitute.com

The three speakers explained that the main underground deposits for the CO2 would be saline aquifers and depleted oil and gas reservoirs (those from which oil and gas have been extracted). There is no shortage of space, with depleted oil and gas reservoirs worldwide being estimated as able to hold over 300 billion tonnes and saline aquifers some hundred times more. The technology needed is the same as that for oil and gas extraction, and in any case CO2 has been pumped into reservoirs to improve recovery for many years. Leakage is minimal in the same way that leakage of natural gas from reservoirs is minimal.

But the technical feasibility of CCUS has been recognised for a long time. In 2016 the UK Parliamentary Advisory Group and the Committee on Climate Change stated that the problem was the organisation, not the technology: who should make the investment and bear the risks? how should they be rewarded? The PAG recommended setting up a government-owned company that would transport and store the CO2 and be paid to do so by the CO2 producer.

That never happened, and in fact worldwide from 2011 to 2017 there was a decrease in CCUS projects under development, as measured by volume of CO2 to be stored. Since then the number has increased but even if all projects under consideration today are implemented the capacity will still be only 110 Mtpa per year, a fraction of the amount needed. The Global CCS Institute claims that at the end of 2020 there were 60 projects at some stage of development, the majority being in the USA or Europe.

In the UK the first industrial scale carbon capture plant will be at Tata Chemicals Europe’s in Northwich, Cheshire. It is due to be commissioned this year with a capacity to capture 0.04 Mtpa of CO2, which will be used in the manufacture of sodium bicarbonate.

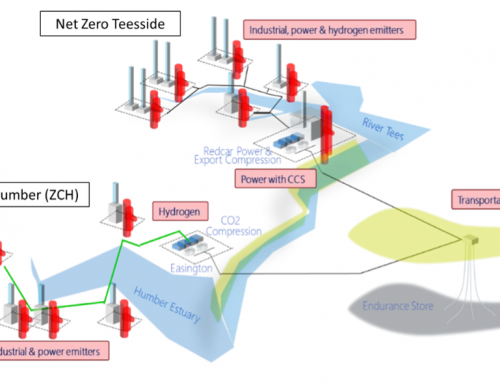

Furthermore the UK Energy White Paper of December 2020 commits to invest £1 billion in CCUS by 2025 hoping to push the UK to be a global technology leader. Most of this will go into four industrial clusters, two of which (Net Zero Teeside and Zero Carbon Humber) started planning over a year ago but will not be operational until late in the decade.

Alongside this, two commercial projects for storage are evolving. The first is the Northern Endurance Partnership of BP, Eni, Equinor, National Grid, Shell and Total to develop transport and infrastructure to store CO2 in the saline Endurance aquifer in the Southern North Sea. BP is the operator.

The second is the Northern Lights consortium of Equinor, Shell and Total that will offer tankers to transport CO2 from a client to a facility in Norway that will store it in a suitable underground formation. While Equinor is the operator, the project builds on an existing state project to store CO2 produced in Norway.

We are therefore starting to see the emergence of a CO2 transport and storage industry, privately run but with strong government support. There are still many uncertainties in the cost and efficiency of the process, and results will only emerge towards the end of the decade, but we are at least seeing movement in the right direction after several false starts.

In the meantime the Oxford Martin Institute is hosting another lecture on 22 March about CO2 storage, this time in the ocean.