Brazil’s Itaipu dam produces five times more power than the two Angra reactors. Image: By muzikantcz, via Wikimedia Commons

This article first appeared on the Climate News Network.Net website

by Jan Rocha

The prospect of more atomic energy for Brazil, envisaged under President Bolsonaro’s nuclear plan, fails to impress many of his compatriots.

SÃO PAULO, 6 July, 2019 − President Jair Bolsonaro’s nuclear plan is leaving many of his fellow Brazilians distinctly unenthusiastic at the prospect not of pollution alone but also of perceptible risk.

A few days ago a procession of men, women and children carrying banners and placards wound its way through the dry parched fields in the country’s semi-arid region in the north-east. It was a Sunday, and the crowd was led by the local bishop. But this was not one of the customary religious processions appealing for rain.

This time, the inhabitants of the small dusty town of Itacuruba were protesting against plans to install a nuclear plant on the banks of the river where they fish and draw their water.

The São Francisco river, which rises in the centre of Brazil and meanders its way 1,800 miles north and east to the Atlantic, is Brazil’s largest river flowing entirely within the country.

Over the years five dams and a scheme to divert and channel water to irrigate the region have severely reduced its volume.

“If Brazil had an atom bomb we would be more respected”

Now the local population sees a new threat on the horizon: a nuclear reactor drawing water from the already diminished river, returning heated water that will kill the fish and bringing with it the risk of accidents and radiation.

So over 100 organisations have come together to form the Antinuclear Sertão (Semi-arid) movement, supported by the Catholic church, to challenge the planned reactor and denounce the risks it would bring.

The alarm was raised when the government’s proposed National Energy Plan 2050 was revealed. It includes plans for 8 new nuclear reactors, the first of them to be located in Itacuruba, and a £3 billion (R$14.4bn) contract to finish the Angra 3 reactor, begun over 30 years ago by Siemens KWU, but abandoned in 1986.

This is in spite of Brazil’s chequered history with nuclear power, and an abundant variety of renewable energy alternatives. Two pressurised water reactors (PWUs), Angra 1 and 2, were built over 40 years ago by Westinghouse and Siemens KWU respectively, near Rio de Janeiro.

Low output

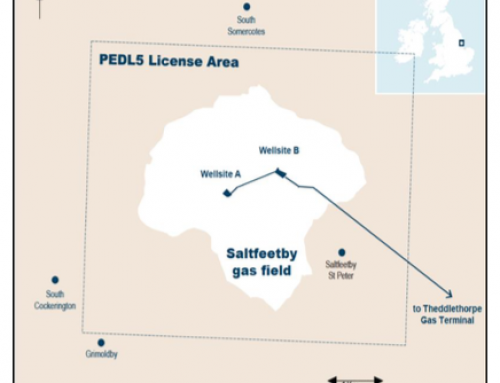

Together they supply just 3% of national energy needs, while Itaipu, Brazil’s largest hydroelectric dam, a bi-national project with Paraguay, alone supplies 15%.

Hydropower provides over 60% of Brazil’s energy needs, and the share of other renewables, wind, solar and biomass, although still regarded as unreliable by the government, is steadily increasing. But nuclear energy remains a cherished dream for some in the government of Jair Bolsonaro.

Leonam Guimarães, president of Eletronuclear, the company responsible for the three Angra reactors (in Portuguese), likes to point out that Brazil is one of only three countries, along with the US and Russia, which possess the three conditions needed for the complete process: it has some of the world’s largest uranium reserves, it dominates enrichment technology, and it has reactors.

For Mines and Energy Minister Bento Albuquerque, finishing Angra 3 “is a priority project.” More alarmingly, one of President Bolsonaro’s sons, Eduardo, a federal congressman, said recently: “If Brazil had an atom bomb we would be more respected” (in Portuguese). Nobody took him seriously, and Brazil did sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1998.

Finishing Angra 3 will cost approximately £3bn. The estimated cost of the proposed new reactor at Itacuruba is £6bn. Nobody knows where the money will come from or whether these figures are realistic. The Brazilian economy is stagnating, with growth at a standstill.

Leak possibility

And what about the risks? Professor Heitor Scalambrini Costa, an energy specialist, said the reactor at Itacuruba would bring risks to the entire São Francisco river basin.

“Installing a nuclear reactor next to the São Francisco river brings the possibility of a leak of radioactive material”, he said. He pointed out that the river passes through 5 states, inhabited by several million people.

The protestors also have a local law on their side. It bans the installation of any nuclear plant unless all renewable sources, including hydropower, have been exhausted. That could be a long way ahead.

Bolsonaro’s government might dream of nuclear energy, his son might even dream of a nuclear bomb, but the law and economic reality are likely to get in the way. − Climate News Network

About Jan Rocha

Jan Rocha is a freelance journalist living in Brazil and is a former correspondent there for the BBC World Service and The Guardian