In 2013 the US Energy Information Association estimated that China has the largest unproved but technically recoverable shale gas resources in the world, nearly double those of the USA. However, development has been slow and only really started with production from the Fuling gas field, southwest China, in 2014. In 2017 China’s total shale gas production was 9 billion cubic metres compared with 472 billion cu m in the US.

There is no lack of ambition in China, motivated by the need to replace polluting coal-fired power stations and to reduce the amount of imported gas (125 billion cu m in 2018). In 2016 the National Energy Administration has set a target of producing 20 billion cu m in 2020, corresponding to 9 per cent of total gas consumption, and between 80 and 100 billion cu m in 2030, representing 15 to 19 per cent of total gas consumption.

Shale gas development has so far been concentrated in the Sichuan basin and has been shared almost entirely by two companies in roughly equal proportions: China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec). Sinopec operate the Fuling field which produced nearly 6 billion cu m in 2018, and is claimed to be the world’s second largest shale gas reserve (the largest being the Marcellus in the USA). Overall there were reported to be 600 producing wells with 700 new wells planned to come on stream by 2020. But given the fast rate at which production decreases in shale gas wells this seems too few.

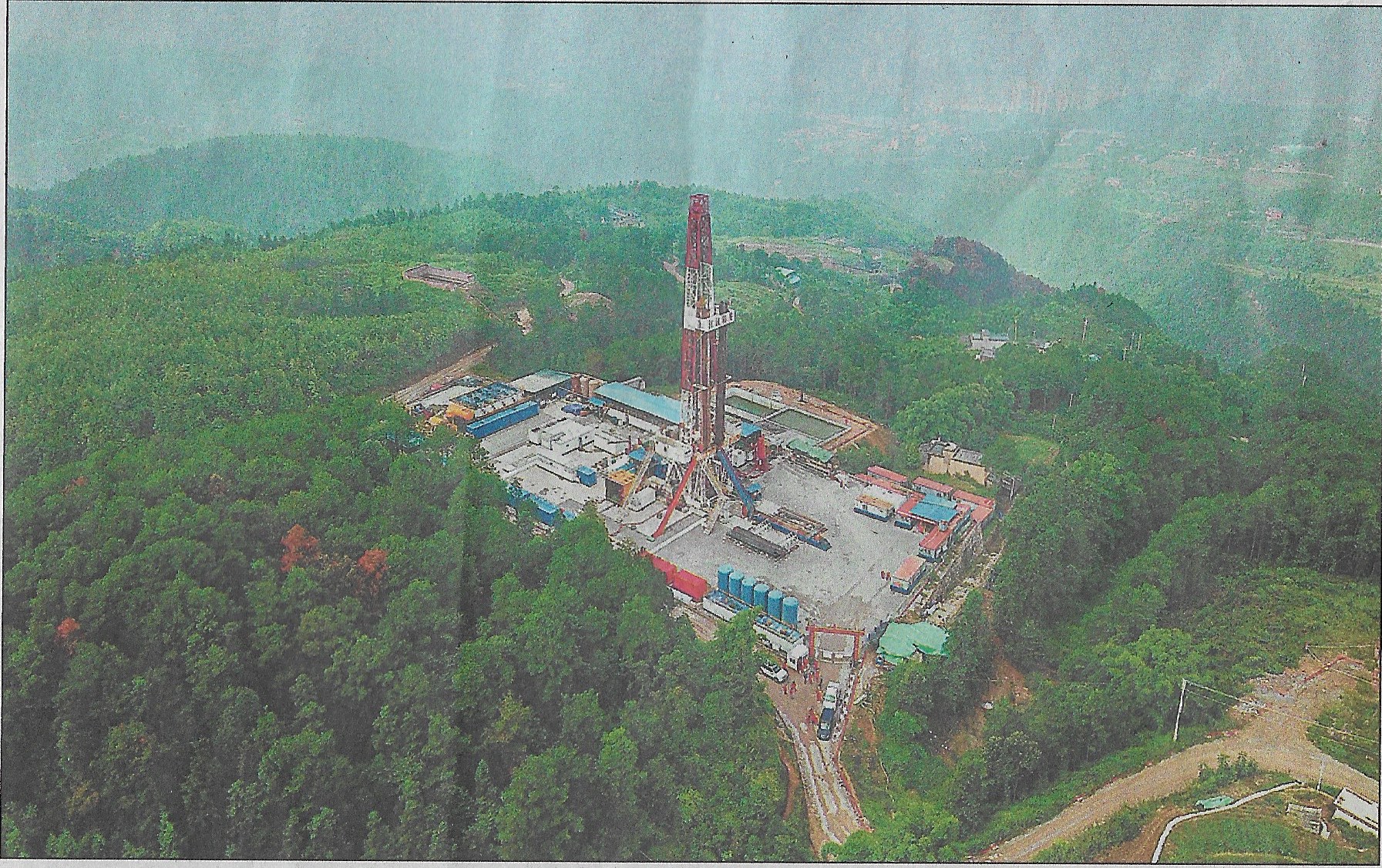

A drilling rig in the Fuling shale gas field in Chongqing municipality, south west China (XINHUA in China Daily)

The production targets would be challenging in the best of circumstances, but conditions in the Sichuan basin are not the best, for several reasons. First, the terrain is not like the flat open plains of the American mid-west. It is mountainous, forested and quite densely populated. This makes for difficult access and causes problems for transportation of drilling and fracking equipment, and for the laying of pipelines. Secondly there is apparently a shortage of water, needed in large quantities for both drilling and fracking. Finally, the underground geology is more complex.

Due to these problems the costs are high and the margins are low. Wood Mackenzie has reported that the companies would find it difficult to break even without government subsidies. Thus, although some smaller private companies are active their contribution is small. The government has tried to encourage more local companies to get involved by holdings lease auctions. However the winner of the last one in 2017 (Guizhou Industrial Investment Corporation) does not have the expertise and would presumably contract it out to experienced operators or service companies. Not much has happened so far.

CNPC and Sinopec are therefore expected to do a vast majority of the work needed to meet the goals. As a result they will gain plenty of experience and will become more efficient and more cost effective in the process.

From the UK perspective the Chinese experience will be interesting to follow because should shale gas development take off here the conditions will often be somewhere between North America and fields like Fuling, with hilly terrain, sizeable populations and tricky access. On the other hand there should not be a shortage of water, but there will certainly be a noisy anti-fracking brigade, something which is unlikely to be seen in China.