The BP Statistical Review of World Energy for June 2017 states that “….there is no such thing as the behaviour of ‘US tight oil’; the Permian is very different to Eagle Ford which is different to Bakken. So beware of generalizations”.

Note the use of the term “tight oil”. Outside the oil industry and in particular outside North America the term “shale oil” would probably have been used. But there are good reasons for preferring tight oil, as can be seen by examining more closely the three reservoirs mentioned by BP.

Before doing so we should define our terms. We shall use Shale as a general word describing a rock that is fine grained and with high clay content. Many shales are source rocks, meaning that they have high organic content which in time matures into oil, much of which then migrates out into the surrounding rocks.

A Tight rock is one of low permeability, so that fluids such as oil and gas flow through it with difficulty. It usually needs to be fractured to produce commercially.

Bakken

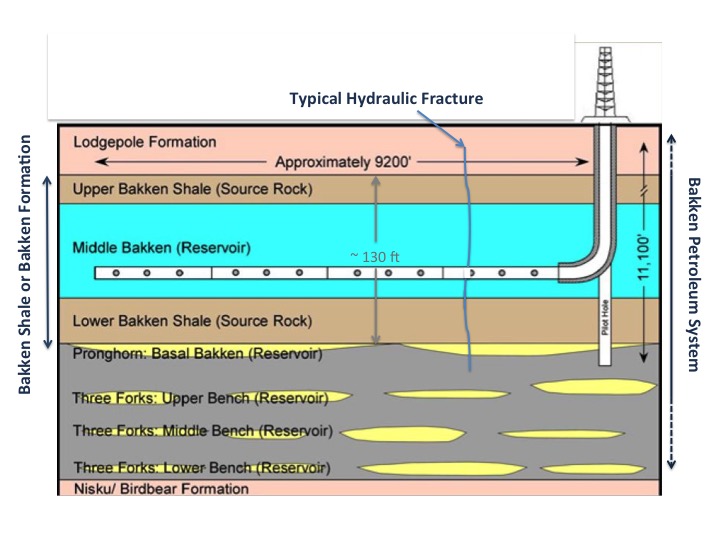

The Bakken in North Dakota used to be called the Bakken Shale but is now more correctly referred to as the Bakken Formation or the Bakken Petroleum System (BPS) or, as in the BP report, avoiding the issue altogether.

Geologists identified the Bakken Formation as a single geological unit, but before the exploitation of oil it was often known as the Bakken Shale because of the two very distinctive Upper and Lower shales at top and bottom.

As shown above, almost all wells are drilled horizontally into the Middle Bakken which is a silty dolomite with low permeability (hence “tight”). Above and below are two shales that have high organic content and are the source rock for the oil. Since the permeability of all three layers is low the rock needs to be hydraulically fractured.

These fractures usually pass out of the Middle Bakken, through the shales and into the formations above and below. Production comes mainly from the Middle Bakken with some from above and below, but very little from the two black shales as their permeability is even lower. Thus it is wrong to call this shale oil, although the presence to the two shales affects the reservoir characteristics.

Eagle Ford

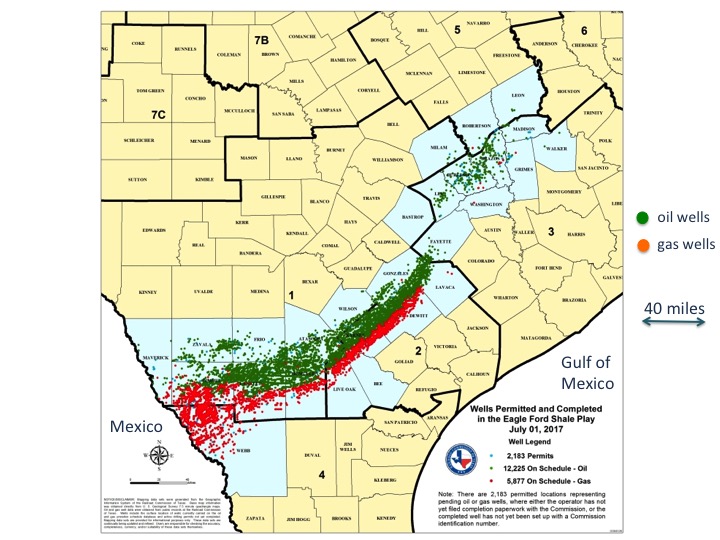

The Eagle Ford geological unit was first identified as an outcrop in the town of Eagle Ford, near Dallas. The outcrop had the physical appearance of shale and contained a large percentage of clay, a key component of shale, hence it was called the Eagle Ford Shale.

Location of the Eagle Ford in southern Texas, showing wells drilled (Railroad commission of Texas, www.rrc.state.tx.us). Note the density of wells.

However the producing intervals are to the southwest, as shown above. Within its 250 ft thickness there are layers of shale source rock inter-bedded with a high percentage of low permeability limestone. The unit is now sometimes referred to as the Eagle Ford Group, or just Eagle Ford.

Permian Basin.

The Permian Basin covers an area of about 250 by 300 miles and contains many oil reservoirs with a wide range of characteristics. Some of them are in formations labelled as shale, for example the Wolfcamp Shale, but like the Eagle Ford this consists of layers of organic shale and low permeability carbonates.

Shale oil vs Tight oil

There are several reasons to avoid calling these shale oil reservoirs.

First, in order to avoid confusion with oil shale. An oil shale is an almost pure shale with high organic content and with immature oil that is still in the process of formation. Oil can be extracted by heating the rock at high temperature. There is a large amount of oil shale in the world, but at present it is not economic because more energy needs to be put in than can be retrieved. Some people refer to the oil retrieved from such rocks as shale oil.

Second, as we have seen, many rocks are called shales for historical reasons, but on closer examination they contain layers of both shale and various porous materials. Oil production comes from the fractures, either natural or induced, and from the porous layers rather than the pure shale layers, although the shale may over time feed some lighter oil into the other layers.

With gas the situation is a little different. There are tight gas reservoirs that are similar to tight oil reservoirs, but there are also true shale gas reservoirs that are predominantly shale but have a significant amount of gas adsorbed on the surface of the clays. This is released into the fractures and the borehole over time and forms an important part of the recoverable gas.

This leads to the third point, which is the public perception of shale. By now people understand that there are large volumes of shale in the earth. While many of the true shales may produce gas, they are unlikely to produce much oil. This leads to overly high expectations and subsequent disappointment.

So we will aim to avoid the term shale oil and recognise tight oil reservoirs for what they are: a low permeability mixture of clays and other materials, brittle so that they can be fractured easily, and usually in close proximity to oil source rocks.

As the BP report says there is no such thing as a simple or unique behaviour for tight oil. Each case is different and fairly special. Other special cases will undoubtedly be discovered but in the meantime we will try to beware of generalisations.