By Barney Smith

On 19 November the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, spoke to, and formally released, plans for a ten-point “green” industrial revolution, the details of which had previously been widely leaked. Overall the plan “will mobilise £12 billion of government investment to create and support up to 250,000 highly-skilled green jobs in the UK and spur over three times as much private sector investment by 2030”. In several cases details of the government’s financial commitment were contained in the accompanying report of the PM’s words, rather than in the ten-point plan itself and there is also a rather more uplifting article written by the PM himself in the Financial Times (FT) of 18 November, which contains some figures not otherwise made public. The plan was widely seen as lifting eyes to a future beyond covid-19. It also constituted a sort of curtain raiser to UNCOP 26, the next UN Conference on Climate change, to be chaired by the UK in November 2021.

Not all the ten points were new; the PM had already announced targets for electricity from off-shore wind by 2030 in his speech to the Conservative party conference. (See Greenbarrel of 13 October). This time he reiterated the target of 40 Gigawatts of off-shore wind, adding that this would quadruple our production, “supporting up to 60,000 jobs”. According to the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), the UK, still the world leader in this area, had a total off-shore wind installed capacity of 10.6 GWT, which included the 1.6 GWT brought on line in 2019. (Interestingly, in this point of the plan there was no repeat of the target of 1GW pledged in the earlier far-shorter speech to the Conservatives to be produced by 2030 by floating off-shore wind platforms, a “Brand new” technology).

From “The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution”, www.gov.uk

Hydrogen was the second point in the plan. Jointly with industry the UK will aim “to generate 5GW of low carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030”. This is to be achieved via funding of “up to £500 million”, with £240 million earmarked for new hydrogen production facilities. The FT article somewhat graphically describes this as “turning water into energy”, but fails to note that current methods of producing hydrogen involve the use of electrical energy or methane.

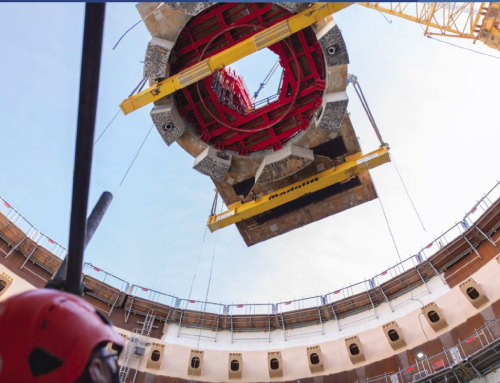

Next, the PM spoke of helping develop both large scale nuclear and “the next generation of small and advanced reactors”, thus perhaps re-opening the possibility of action on small reactors, which the previous government had excluded. £525 million seems a lot to commit to this, but it needs to be seen against a potential bill of at least £22 billion for the construction of Hinkley Point C and an unknown bill for Sizewell C. To this must be added the NAO’s estimate of an additional £50 billion to be paid by consumers for the electricity to be generated by nuclear power.

On electric vehicles, the plan itself contains words about backing our “world leading” car manufacturers “to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles” and “transforming our national infrastructure to better support electric vehicles”. But the PM’s accompanying remarks, and the FT article, record a firm commitment to the ending of the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030, some ten years earlier than previously envisaged. (This will align the UK with Norway, the previous front runner in this field). £1.3 billion was also promised to accelerate the rollout of chargepoints for electric cars in homes, in streets and on motorways; £562 million in grants to help purchasers of electric cars; and nearly £500 million for the development and mass production of batteries for electric vehicles. The FT article makes the total expenditure slightly greater at £2.8 billion, which is a sizeable sum for a government, even if it looks modest by comparison with the sums potentially available from industry and the amounts of cash needed if the targets set by the Paris agreement are to be reached.

Apart from the £20 million earmarked for a competition to develop clean maritime technology, the next couple of points in the plan, on Public transport and on Jet zero and a greener maritime are both worthy and very general. So is the penultimate section on nature, which does however contain the target of planting 30,000 hectares of trees every year.

But in between there is a target on carbon capture and storage for the UK to become “A world leader” in this fashionable technology and a commitment, at least in the FT, to invest £1 billion “in clusters across the North, Wales and Scotland”. Some will remember that the Treasury has twice cancelled earlier competitions for carbon capture, the second also for £1 billion.

Next there are in the PM’s speech both a commitment to invest in 2021 a £1billion to make homes, schools and hospitals “greener” and a further commitment to use the £1billion energy innovation fund already announced “to help commercialise new low carbon technologies.” Boris rounds off with talk of “Developing the cutting-edge technologies to reach these new energy ambitions and make the City of London the global centre of green finance.”

What to make of all this? The PM is good with words and he has definitely had an impact. But a proper evaluation will depend on future actions and expenditure where the PM’s reputation is, to say the least, less well-founded.